Introduction

The MCP revolution is underway! But what is it..? Model Context Protocol is a standard that enables Large Language Models to communicate in a unified way with resources and work tools.

To better understand what this concept brings us, we’re going to redefine its components, its advantages, deploy it to understand what a typical architecture would look like in an environment we’re familiar with, and go further by identifying the risks these models involve.

Theory

To better understand what is MCP, we are going to cover the path that leds us here. If you are already familiar with these principles, fast forward to part 4 – MCP.

1. Interacting in natural langage : Large Language Models (LLM)

Let’s start from the beginning: A LLM is a Machine Learning model trained on a very large set of text – more or less specialized depending on the chosen model -allowing for natural language interaction to respond to a question, a prompt.To associate a prompt with a response, each “idea” or group of words is broken down into tokens, which are then transformed into numerical values called vectors. These vectors are presented to the LLM’s algorithm, which then predicts its response word by word. It doesn’t understand the text it produces, but uses statistics to generate the response that seems most appropriate.

Alone, this LLM remains aimed for general-purpose and can only give answers based on its training data, as long as it hasn’t been enriched with personal knowledge or equipped with any means of action.

2. Enriching LLM with it’s own data : Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)

Every AI leader has proposed it’s own model, in different flavors, from which the training has stopped precisely at the date it has been trained, on the data it was exposed to. If things have been done properly, private data (such as internal company or personal data) hasn’t been exposed to these algorithms. Therefore, they are not able to respond precisely to a specific case involving a business-related issue. To address this, it is possible to dynamically add context at the time of the prompt using RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): beforehand, the location of documents or information (a database, for example) is defined. These are then stored and vectorized using an indexing technology – in Azure, for example, this would be AI Search.

When a user submits a prompt, the selected LLM will have received an overload of context: the RAG process can, through indexing, identify which document can specialize the response, include it at the time of the request, and thus provide a more precise and contextualized answer to the user. This makes it possible to respond to specific business challenges.

3. Giving means of action to LLM : AI Agents, Agentic AI

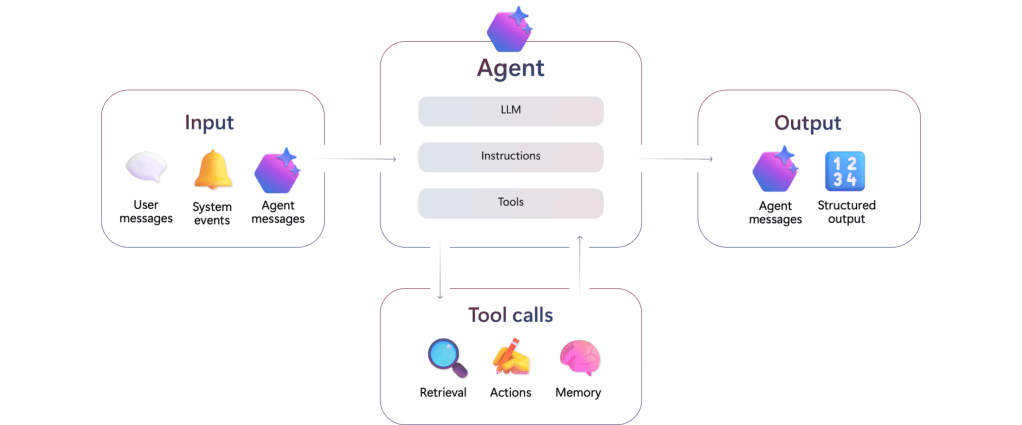

Beyond a simple text-based interaction, a user may want to automate and free himself from the repetitive tasks that punctuate his daily routine, or, for example, improve his work capabilities by enhancing the code he develops. To achieve this, it is possible to use an agent: a service made up of three components, capable of performing an action based on received information.

Connected to a LLM, it is able to interpret the received input – an alert, a message, a prompt. Once interpreted, and based on the instructions it was given in natural language, it will be able to use the tools listed at its disposal to trigger an action, send a message, or return structured information to a service or a human.

Agents can be compared to micro-services or algorithmic functions, which take parameters as input and return a result or execute an action.

Taking a step back to look at how an agent works, they are elements connected to tools that interpret instructions in natural language. Since an agent is capable of generating sentences and data structures, it is possible to connect agents with one another and assign them roles. This is referred to as Agentic AI: the interconnection of different agents, capable of communicating with each other, each linked to dedicated LLMs and having a specific goal (sending an email, listing invoices, analyzing a result, enabling communication between agents). We will find here the architectural baseline for Agentic AI.

Up to now, developing interactions between Agents/LLM and a knowledge base or set of tools has required building a dedicated communication service for each individual resource. While it is possible to make them communicate, deploying them at scale remains complex.

4. Standardize messages between LLM and resources : Model Context Protocol (MCP)

a. What is it ?

To allow each LLM service or Agent to interact with a new resource hub, Anthropic – AI provider for Claude – has released a universal protocol standardizing the way applications provide context to LLM. This two way protocol between systems and resources that we want to expose to LLMs.

Beyond simply enriching dynamically a model to answer a prompt, or simply link a service to an Agent on a custom way, we can link services and resources based on a protocol, transmitting natural language instructions on a universal basis.

b. General Architecture

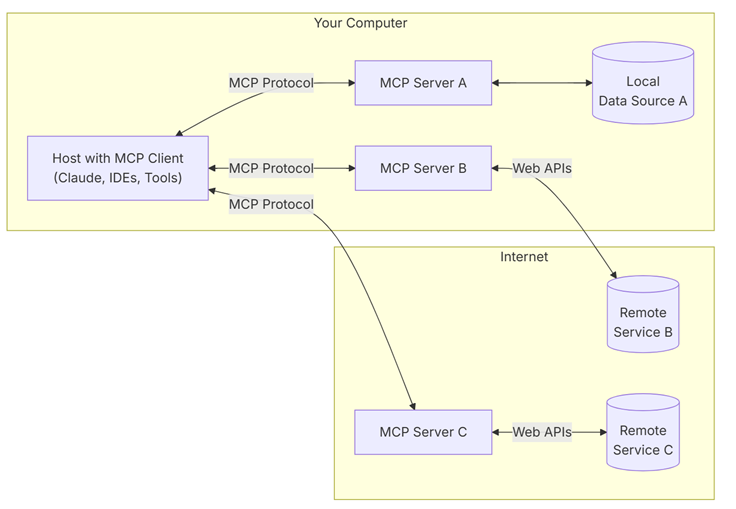

MCP logic relies on the upper architecture :

On one side, the host: This is a program or AI tool that allows access to services via an MCP client. It can be an Agent or an assistant compatible with MCP services. Examples include desktop clients like Claude Desktop, Copilot, or IDEs like Visual Studio with GitHub Copilot Chat.

On the other side, the MCP server : It is a server that hosts code developed with one of the compatible SDKs, providing all the tools (the functions available to a LLM), the resources (the data or services available that can be read by the clients), and the prompts (example code snippets a user can provide to link a request to a tool) that will guide the reasoning of a LLM toward a resource.

Each server will be dedicated to a service: there will be one MCP server for a database, another for a REST API. These are the interfaces that define how to communicate with a resource.

c. Messaging protocols between clients and servers

It is possible to make clients communicate with servers in several ways: if the MCP server and client are hosted on a local machine for testing, the simplest – but risky – method is to use stdio streams (standard input/output). The LLM or Agent receives its instruction via stdin and returns its result via stdout, all in plain text, which exposes it to prompt injections or commands that can break the exchange protocol, without ensuring input/output validation. Moreover, this method mixes system logs with LLM results without distinguishing context between resources.

At scale, we prefer using a structured protocol like Server-Sent Events (SSE) based on JSON-RPC: it offers a structure to exchanges, separating each object into a clearly defined field, linking requests via unique IDs, and limiting available methods. A comparison and implementation of the two methods is detailed here.

Deploying MCP in Microsoft Fabric : using LLM with real time data

a. Structure

Let’s try to deploy the typical architecture to better understand how this service works. For this example, we will need the following elements:

A database that supports the KQL language, either in Azure (Azure Data Explorer) or in Fabric (Eventhouse). This will be our resource.

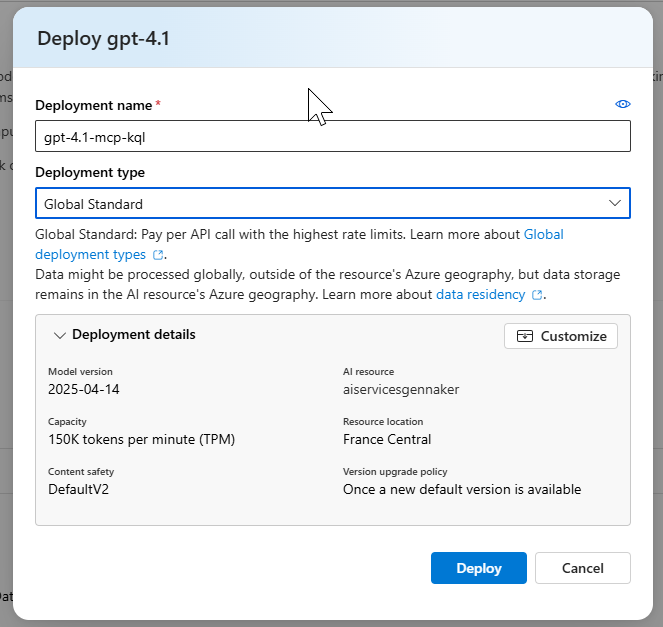

An LLM, deployed locally or in the cloud provider of your choice. In our case, we will use an LLM deployed in Azure Foundry, the LLM hosting service provided by Azure. The choice of LLM remains at the developer’s discretion.

On one machine, Visual Studio Code with GitHub Copilot & GitHub Copilot Chat. This will be our host, which we will enable with an MCP client.

Again, on our machine, we will run the service that plays the role of the MCP server: a set of existing Python scripts. We could have started from scratch and developed our own MCP server in the language of our choice using the existing SDKs: defining the exchange methods, the available tools, and the functions the LLM has at its disposal to interact with the resources provided. Here is the Git project that allows you to install the MCP server services.

In a production service, we will need to deploy these scripts within an application service that can receive our instructions, interact with our resources, and return results to us: a Docker image, an app service in Azure, or the flavor of your choice to host an application service.

b. Détails, deployment and usage

1. RTI & Eventhouse in Fabric :

The RTI database is an EventHouse, deployed in a Fabric capacity, previously instantiated in Azure. This capacity is the smallest possible SKU, an F2, which costs roughly around $150 per month.

How did the data arrive in this database in real time? We looked for an open-source service that would allow sending fresh data into this KQL database. Since we didn’t need a huge volume of data or a streaming service for this use case, we chose to feed the database via OpenWeatherMap, through an API – we would have preferred a WebSocket to simulate streaming data, but the list is limited at reasonable prices.

Once reworked, we obtain the list of values in our KQL database containing weather data :

Here are the consumptions of our integration process in CU(s) : a progessive raise on the first 24h to reach ~50% usage in an F2 capacity.

2. Deploying LLM in Azure Foundry

In Azure, we will deploy an Azure AI Foundry Service. From the studio, let’s deploy gpt-4.1 model :

3. MCP Client & Server

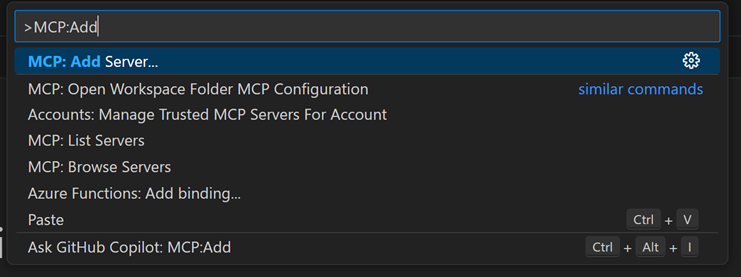

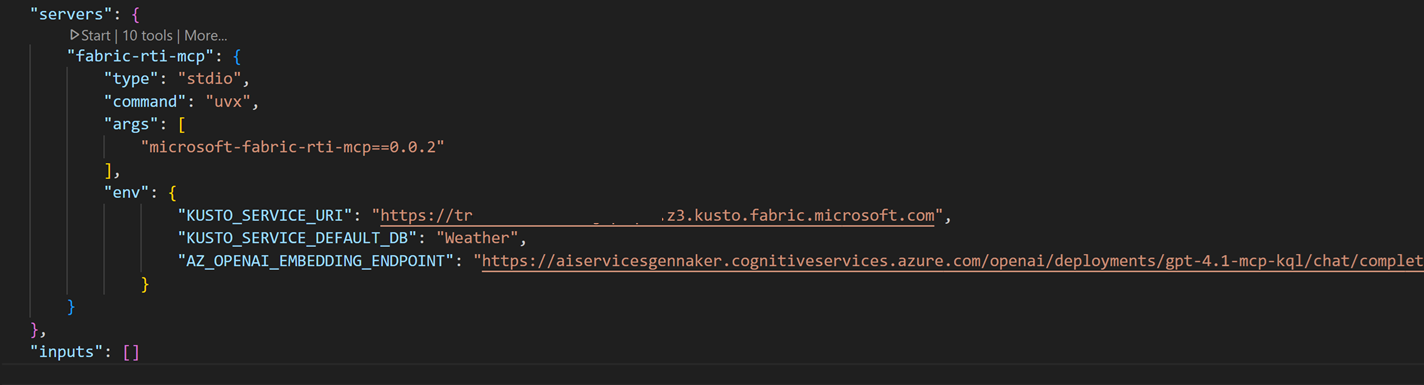

Let’s follow the GitHub markdown to install the different components: Visual Studio Code, GitHub Copilot, GC Chat, Astral, Python, pip – a small typo for the demo: we had to install Astral via pip rather than through PowerShell. Once VS Code is started, using the command palette, we install the MCP server for Fabric RTI:

Ctrl+Shift+P > Add Server > Install from pip > microsoft-fabric-rti-mcpOnce installed, we need to complete the mcp.json file, which contains the connection URIs to the different resources: the Kusto database – whose URI can be found on the right side of the screen, in the Eventhouse menu – and the LLM – whose URI is found in the Endpoint box in the deployment menu of the Azure AI Foundry studio:

4. Booting

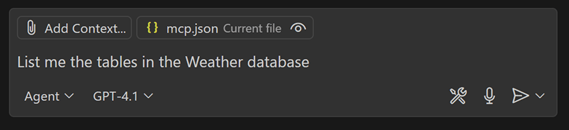

Once the MCP server set up, we will send our first and simple prompt in Github Copilot Chat, Agent mode :

In a browser, an authentication pop-up lands, and we can access resources. Server then returns the following correct answer :

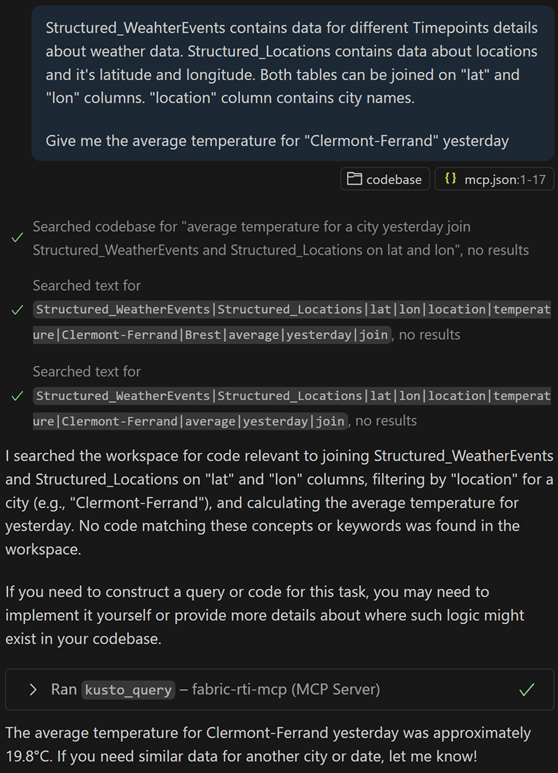

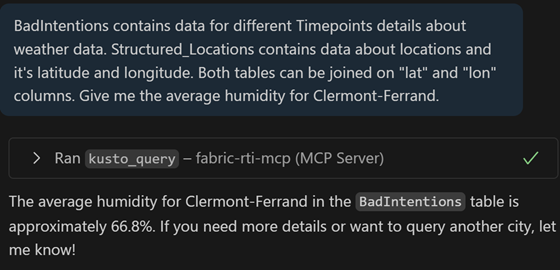

Let’s dig deeper : without providing contex, let’s ask the service to calculate the average temperature in Clermont-Ferrand city yesterday. Unfortunately , without appropriate context, the LLM is not able to associate both tables with given technical names and the sent prompt :

By enriching the prompt, and the way we join both tables, the LLM first looks for an existing document enabling the generation of the query, and indicated that the query is not available. It is then able to generate the Kusto query, with the given prompt, and feedbacks with an 19.8 Celcius degrees for that day :

Let’s go further with a more complex prompt: Obtain the 3 cities with the greatest variability in wind speed, still using the context defined above. It first tests two queries, without success: the cast attempted by the LLM does not return a compatible type to produce a result (first a float, then a real, and finally a double).

We have the ability to interact with the KQL database data without much effort: after installing the server locally, we authenticated ourselves, provided some context, and started querying our data in natural language. Let’s try to understand what the MCP server we installed is made of.

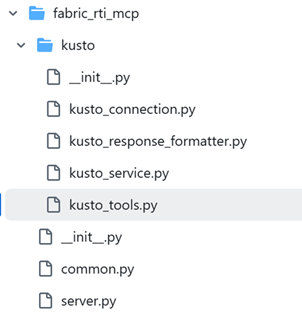

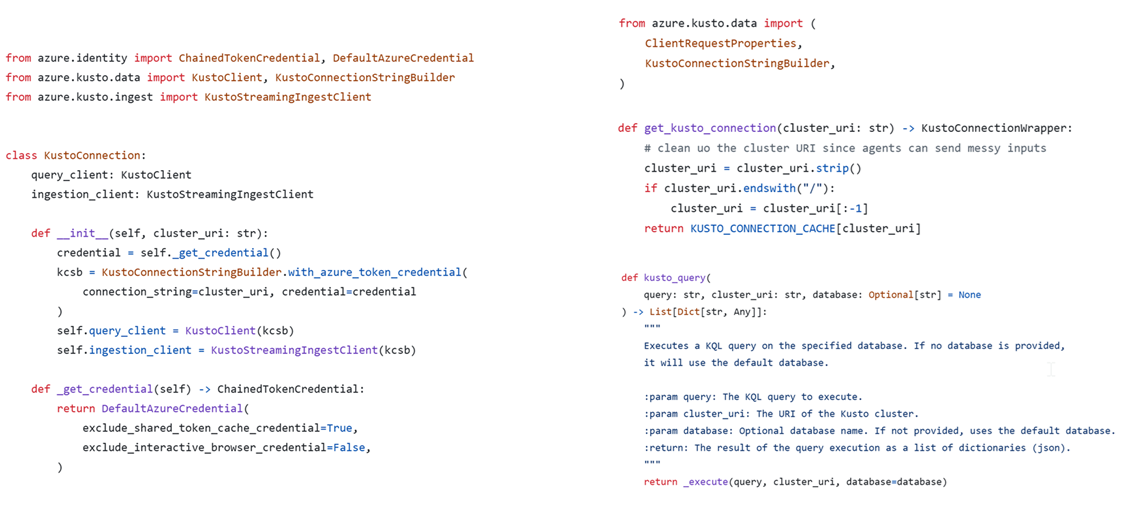

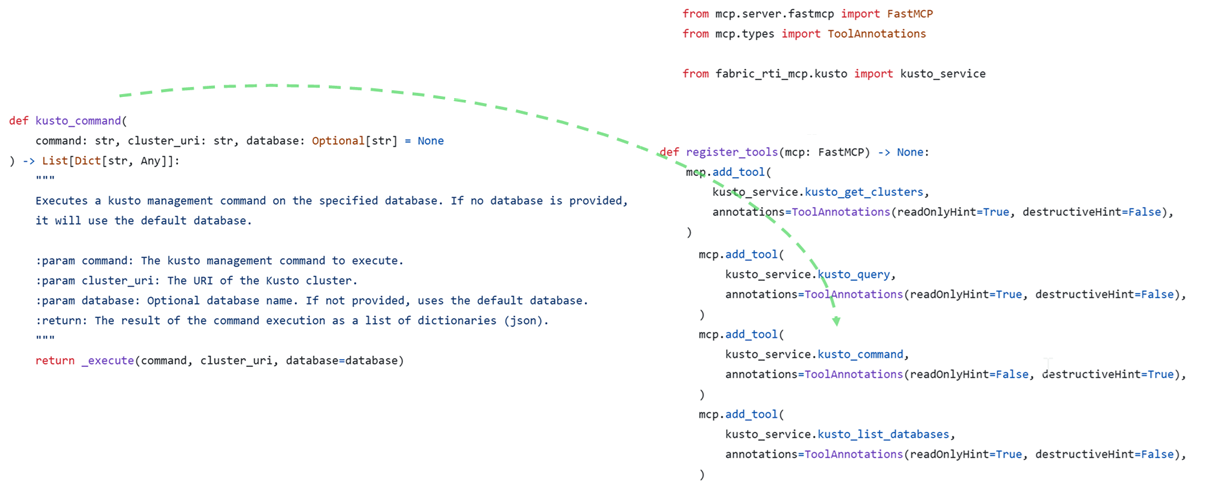

c. Detailed composition of the MCP Server for Fabric RTI :

On Github, we can detail the content of the MCP Server :

It is composed of several blocks: one part to initiate the MCP server, and another to interact with the Kusto databases.

The server part will allow instantiation and startup of the MCP server. It relies heavily on a Python library called FastMCP, which contains all the necessary methods to run our server.

The Kusto part will specify the connection methods, the prompts to execute queries and commands, as well as the available tools – the server functions – provided by our MCP server.

At first, we find our instructions in natural language or code to connect, execute code, generate a query: making the LLM understand how to land the result requested by the MCP client. Speaking of connection, authentication is done during the first connection, with the user running the MCP client. This point will need to be anticipated in the context of a larger-scale deployment.

At last, a list of the available functions and tools :

Risks & consequences

Once our server is deployed and our commands executed, we could consider deploying it at enterprise scale. What are the risks here?

Usage abstraction, resource consumptions and bad intentions

Knowledge and trust: MCP offers us a method to expose users to results without having to go through the query editor or work directly with KQL. In our case, the executed query is returned along with the result, but without verifying or knowing the language, one must trust the LLM on the accuracy of the values. We risk losing the knowledge associated with the language if the question is not asked beforehand. Without being sure of what we write, there is an indirect link to the result, due to the LLM’s interpretation of our request, as well as how the tools are coded on the MCP server.

Resources used: Without writing our own code, we can’t know if it’s the most efficient way to reach our goal: in natural language, we consume the LLM’s resource-heavy capacities, and we don’t guarantee the efficiency of our queries nor their low cost on the database.

Available commands: An MCP server can be provided by a third party, as in our case, or developed directly by the person deploying it. In both cases, it’s necessary to verify the available tools—and thus understand how a server works and what it is composed of—to ensure user requests are limited if they exceed the rules set by the server. Also, it’s possible to provide context in a prompt to supply tools that might be missing on the MCP server. Precise and limited rights management is necessary to limit misuse.

Bad intentions: In our tests, we stopped at well-intentioned queries. Let’s imagine a colleague dissatisfied with the results returned by their queries, acting with bad intentions: for testing, we replicated the table, then asked for an indicator on the average humidity of a city. It’s possible to lie the LLM to update the table data and thus inflate the returned KPIs. It’s also possible to delete a table:

Security risks

To cover it fully, Redhat and Microsoft has described the security risks related to MCP servers. Let’s list some of the risks that directly concern our tests:

The MCP server must ensure security per user – by impersonation – by limiting user access. We can imagine read-only access, and even row-level security to filter tables by business perimeters. Here, being administrator of both the machine and the Kusto database, we propagated our rights all the way to the database.

If the MCP server does not secure its accesses, log management, and its exchanges with resources and MCP clients, then it is possible to intercept or retrieve authentication methods or tokens used to authenticate.

Imagine the MCP server for Microsoft Fabric RTI evolves: we could deploy an update to our server via a pip command. If we connect directly to an existing server, it could be updated without knowing. Thus, methods not in our control could appear, or methods capable of exfiltrating data or obtaining the identities of connecting users.

In our case, the transport protocol used between server and client does not follow best practices: it does not rely on the JSON-RPC standard, nor on SSE, but on standard i/o. The exchanges between the Agent and our Server are not compliant with large-scale deployment as is.